Grail quest*

A year ago (or maybe more) I saw some ceramic beakers through a shop window in the tiny village of Cucugnan over in the Aude, sitting under the shadow of the ancient Cathar stronghold of Queribus. I’ve been meaning to go back and get them ever since, but there’s not quite been time. So last Saturday morning, with a rather vague plan and a sense of ‘if not now then when’ I set off for Cucugnan on my bike. The map said 67km away - not too bad until you consider the return trip total.

Sometimes it’s best not to think too hard. The mileagel, once added up, is quite ambitious for an unplanned morning ride but the potential of rolling out, off, and far away is too good to waste. Wisdom is all well and good but from time to time it needs to take a break.

Wrapped up in leg and arm warmers and a gilet for the morning chill, with my handlebar bag stuffed with bars, a jacket and a tiny portable bag for shopping (just in case the pottery was open), I was as prepped as I know how.

It’s easy to get rolling here, downhill for the first few kilometres in the shadow of the valley. It doesn’t pay to think too hard in the fast, cold, morning shade. You can already feel (if not see) the lure and promise of rapid sunshine as the slopes open up to the plain beyond. My route wasn’t on the plain though, it was to work my way round the foothills of the Pyrenees that form the natural forts and refuges of the landscape’s earlier inhabitants, until I was well and truly in a different kind of countryside.

Off, out of the valley and away

The first climb is the key to this other land - up through the rocky, sand-coloured pass that sits on the south side of Lake Vinça, rising past a shrine painted on the cliff face and climbing steadily along a gorge, through woods and rocks until it opens onto the wine country beyond. This vast hinterland of farmland and heath lies before me, a vista of hamlets and villages barely connected with spidery tarmac traces of roads. I spot a much-patched gravelly short cut that winds me onwards, through vineyards, golden with turning leaves. This is a patchwork landscape shaped by viniculture. It feels like I’ve been lifted up into it, closer to the sky. A place where everything is brilliant, the clear autumn air luminous with glorious sunshine.

High.

From here it’s a succession of terracotta-roofed villages, each typically built tightly around a tower, fort or church that sits atop a mound. The narrow streets of houses wrap around this high point to form a pale peach and russet cone that stands out against the greens and golds of fields and trees.

The signposts match the map so I point my bike towards Cassagnes. The route keeps me high up, and the landscape drops away from me into the valley below. I’m treated to views out over the lake of Caramany and the forests and windmills beyond. Nothing is too steep or slow and I can keep pressing on at a pleasing tempo - with every passing kilometre it seems more likely I’ll make it to Cucugnan.

The next waymark is Latour-de-France (which always amuses us… there’s an actual French town with the same name as the annual biggest bike race in the world). I almost head out of town in the wrong direction but a quick bit of navigation and I reroute across a (dry) ford and back on to the road heading over towards the Aude. There’s a quarry cut into the rock on the hillside, the same pale orange and rose of the villages, a reminder that this is a landscape sculpted by humans for generations.

Vines and rocks

At this point, I have only 16 km to go, according to Google. But I miss the turning for the cycle lane and end up on the main road to the wine town of Maury. This is the least pleasant part of the ride. A long, straight and traffic-heavy highway. I can see the climb up to the castle of Quéribus slanting across the towering limestone grey of the cliffs ahead though, and decide just to keep my head down and push on despite the traffic, taking the simple route towards it rather than search for a shortcut and risk getting lost in the foothills and dirt tracks between vineyards. Once I reached Maury, mercifully alive despite the busy road, it proved straightforward to find the turning to Cucugnan, with the village itself signposted at last.

The climb is measured out by the green-topped cyclists’ markers found all over France, handily detailing the distance to the summit, gradient and altitude. To my delight there is a view of Canigou on the horizon to my right as I climb. There’s a dusting of snow visible on the peak even at this distance and I feel as though I have company from home.

The road ahead is steepening…

Ahead, the pale mass of Quéribus is perched on the steep slopes above the col, part rock-face, part human hewn, a stronghold for at least a thousand years. Whilst I can imagine the turmoil that inspired building this fortification, the col itself is undramatic. Hungry and intent on my goal I barely and fleetingly consider turning off and up to the fort but postpone it for another day when it may figure as an extra climb.

The road ahead - with Quéribus at the top

Instead I head straight down the hairpins into Cucugnan, keen for lunch and to see whether the pottery is open. There’s a windmill atop Cucugnan which marks my bearings, up through the village’s tiny steep ginnels. The pottery appears, just as I remember it, on my right. The door, straight off the street, is (amazingly) open. No time to waste, I leant my bike against the wall to scuttle in, slightly incredulous that the tenuous mission had become more real.

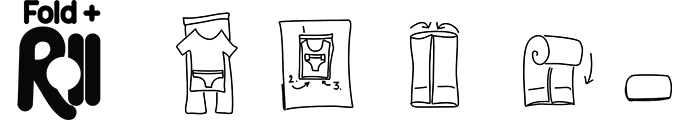

Inside, there were all manner of beautiful ceramics, with the signature rough cast blackened exterior and glazed inside that had drawn me originally. Some quite glorious bowls caught my eye. But all I wanted - in fact all I calculated I had room for in my handlebar bag - were two cups. It took me a few minutes to choose between the different swirling colours of the interiors. The options were all magical, but eventually I chose one with the blue of a frosted winter landscape with flakes of white like a snow laden cloud, and another with a spiral of a deeper cobalt-heavy glaze that had more in common with a warm summer sky. The potter packed them into paper and closed his shop for lunch as I put them into my spare bag to carry up to the windmill - which is also a bakery.

So hard to choose…

The fact that it was lunch time in France meant that (like the potter) all small shops shut. Bakeries too. As I sat down disconsolately, under the windmill, pulling on my jacket against the strong breeze to wait (and reflecting ruefully that, of course, a well-situated windmill would be in line with the wind), one of the staff took pity on me and paused from her lunch break to make me a coffee and sell me pizza and cake. Once I’d inhaled all the pastries I could, I emptied my bar bag and set to repacking it with the cups. I seem to have a nervous tick of adding a couple of extra bars ‘just in case’ every time I go out for a ride, so the main job was to squeeze about a thousand calories in bars and gels back in around the packaged cups.

Treasure, buried in a bar bag underneath bars

I wasted no time in getting back on my bike - the map estimated nearly 5 hours to get home and it was already 2pm. There was no alternative to heading back over the Quéribus pass and thence down towards Maury. But as I reached the edge of the town, a sign to one of the vineyards - Mas Amiel - caught my eye. I was sure that it wouldn’t be a dead end as Mas Amiel was a domain you could see from the main road - with its initials cut into the hillside - so I followed it. This was one of my better ideas - the ‘road’ turned out to be a superb rural cycle way with a perfect surface, snaking its way through vineyards with no traffic and only the occasional other rider. I could glimpse the cars on the main road from time to time and eventually emerged just as the highway crossed the river, with the quarry I’d seen on my way out providing a reassuring landmark in the distance.

Rural cycleway heaven

I was quickly back on the road to Latour-de-France. I knew the route from there would climb - and it did. Not continuously but I was pleased when I was back high up and looking out over the familiar lake and landscape of Caramany. My main worry was water - I’d not filled up in Cucugnan - and was running low.

French villages commonly have water fountains and just as I came to Cassagnes I stopped the only person on an otherwise empty high street and asked whether he knew of one. It turned out to be just up the road. The tap was at knee level sunk into a stone slab by the war memorial. I laid my bike down very carefully, conscious that I was carrying ceramics (however well wrapped) for which crashing and clumsiness would not be ideal. One press of the faucet provoked a surprisingly abundant flow of water. I gulped as much as I could and refilled my bidon. All was well.

Water stop

The only time I missed a turning was in Montalba-le-Château, where I misread the signpost and ended up descending down a wide highway that would have taken me to Ille-sur-Têt and an extra 10 km away from home. Until now Canigou had hovered on my horizon, the guarantor that I was on the correct route - but now it was out of sight and I was in danger of adding a long detour to my day. I talked down my reluctance at the idea of stopping and retraced a couple of kilometres uphill to set myself back in the right direction. The extra climb made me suddenly impatient with the rolling countryside and keen to get back into my own valley. The correct route was - fortunately - a route that quickly began to trend downhill. With Canigou back in my frame of vision I gathered ever more speed, until I was flashing between the crags that edged the very first climb of the day. I was relieved to emerge into warm sunshine by Lake Vinça and start the final leg home.

The slant of early evening sunshine and the increasing languor of sore legs marked the last 20 km. Every little hill seemed to have grown longer and steeper in the intervening hours and the headwind served to slow me down further. My phone battery was on its final few percent and I sadly felt that I was probably in about the same state. I have not been training for long rides - this was a whim, a ‘maybe I’ll make it, maybe not’, devil-may-care ride. But I had my pots and I needed to press on and hope. Back up the cycle path that circumnavigates the town of Prades, through the rocky steep-sided valley where the Conflent passes Villefranche and right onto the road that passes my front door. I know every bit of this last stretch, where it steepens and how it curves over the bridge over the Rotja and each pitch as it passes from lower to middle to upper Fuilla. I had to grit my teeth at every (really quite tiny) slope. It probably only climbs a couple of hundred metres but I felt that every one was a battle.

Bearing treasure

When I finally rolled onto our gravel, Chipps met me at the door and helped peel me off the bike. Quest quested. A bit of a whim turned into a hundred kilometres and more. Sometimes sensibleness can step aside. I’ll take that day with all its unplanned glory. All the sunshine and skies, the wind in my hair, the rolling wheels and feeling of a dare dared. A win won. All brought home, wrapped up and made real in two ceramic cups.

Grails.

* a grail quest is a search for some prize for which you must struggle… it amused me when I realised that, unintentionally, I had brought home a couple of chalices from a realm linked with historical mysteries and knights of the Middle Ages. As is the nature of the grail quest stories, much of the true meaning is in the journey not the goal.