The history and mystery of colour naming

That's not a Pantone chart!

My grandpa, born in the last gasp of the nineteenth century, went on to be a colour scientist in the textile industry. In the 1940s he worked for CPA (the Calico Printers Association) at the Buckton Vale works in Carrbrook, a village to the east of Manchester.

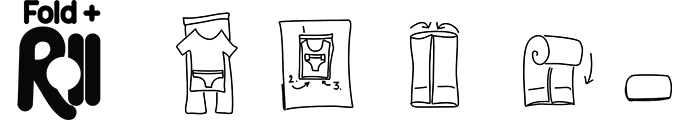

Whilst I was thinking about how to describe the colour options for the new edition of Fold+Rºlls, I remembered that I had his reference book from his days working in the print works. I’ve kept it very carefully in my bookcase, just occasionally lifting the tissue coverings to peer at the coloured plates, mindful that it’s a fragile thing over a century old.

The original colour bible - and three new colours of Fold+Rºll

Color Standards and Nomenclature, Ridgway, 1912

Robert Ridgway (1850-1925) was an ornithologist and full-time curator of birds at the United States National Museum. There’s a strong appreciation of the natural world - and the need to identify and describe it throughout the preface and prologue which precede the plates.

I’ve not read the text before, but reading it today has made me smile. It’s a discourse that maps the struggle of describing and communicating our intricately beautiful and varied world to each other. It grapples with our need both for richness and standardisation, for awe and understanding and for precision and poetry.

The first colour standardisation Ridgway produced (in 1886) was intended as aid to zoologists and botanists who were discovering and studying the natural world. His second, more comprehensive work, published in 1912, and the one I have to hand is an expansion of that classification and standardisation to remedy the ‘inadequate number of colors represented and their unscientific arrangement’[preface].

In theory all our colours can be placed on a spectrum, an infinite gradient of transition from one hue to the other, with a further dimension of paler tints and darker shades that mirrors our experience of bright illumination and darkening shadows - or admixtures of black and white. It is this idea of the solar spectrum that informs the arrangement of colours and of the book.

Where judgment and decision come in is in where to draw the lines in this smooth scale to divide it into nameable parts, working out what is practical, how different the colours need to be in order that we - as humans - see them as sufficiently distinct to merit different words.

“Distinctions of hue appreciable to the normal eye are so very numerous that the criterion of convenience or practicability must determine the number of segments into which the ideal chromatic scale or circle may be divided in order to best serve the purpose in view. Careful experiment seems to have demonstrated that thirty-six is the practical limit, and accordingly that number has been adopted. “

Armed with a theoretical scale, Ridgway progressed to working out the practical struggle of reproducing the scale with the pigments available in the 19th and early 20th century.

“The colouring of a satisfactory set of disks to represent the thirty-six pure spectrum colors and hues was a matter of extreme difficulty, many hundreds having been painted and discarded before the desired result was achieved. Several serious problems were involved, the matter of change of hue through chemical reaction of the combined pigments or dyes (especially the latter) being almost as troublesome as that of securing the proper degree of difference between each adjoining pair of hues.”

Using these discs he constructed a spectrum sequence with intervals in which connecting colours could be accommodated to represent an apparently even transition between the 36 pure spectrum colours, carefully measuring the combinations of colour to achieve each point on the sequence.

Whilst the mapping of the colour spectrum was painstaking science, the naming of parts was largely art (with a measure of natural history). Ridgway recognised that we need descriptive language to identify colours and use them in practical settings - for instance for zoological and botanical description. Avoiding colour names and using only symbols and numbers, he noted has been ‘devised but all have been found impractical or unsatisfactory’.

“The author has taken the trouble to get an expression of opinion in this matte from many naturalists and others, and the preference for colornames very greatly predominates; consequently, whenever it has been possible to find a name which seems suitable for any color in this work it has been done.”

For this he drew on previous naming conventions and nineteenth century ‘standard works’. There’s a romance to this collection - it spans several countries and wraps in a florist’s guide and the catalogues of artists’ materials supplies. The credits include the 1821 Werner’s ‘Nomenclature of Colours’ through Saccardo’s ‘Chromataxia’ of 1891, Mathews’ ‘Chart of Correct Colors of Flowers’ (American Florist, 1891), Lefefévré’s Matières Colorantes Artificiales’ (1896) and the educational colored papers of Milton Bradley and Prang.

Despite being a colour magpie hoarding an enormous collection of coloured materials - from selections as broad as the Winsor and Newton artists’ oil, water and dry colours to a splendid collection of coloured Japanese silks from the company of Woodward and Lothrop - Ridgway was not so impressed by commercial naming activities.

“For obvious reasons it has, of course, been necessary to ignore many trade names, through which the popular nomenclature of colors has become involved in really chaotic confusion rendered more confounded by the continual coinage of new names, many of them synonymous and most of them vague and variable in their application. Most of them are invented, apparently without care or judgement by the dyer or manufacturer of fabrics, and are as capricious in their meaning as in their origin ; for example : Such fanciful names as “zulu,” “serpent green,“ “baby blue,” “new old rose,” “London smoke,” etc., and such nonsensical names as “ashes of roses” and “elephant’s breath.”

Even though he eschewed the frivolity of Elephant’s Breath and Ashes of Roses, there’s a huge dictionary of diverse colour terminology within the pages. From an articulation of ‘drab’ in all its forms - light ecru drab, pallid vinaceous drab, cinnamon drab and dusky drab are the most exotic - to those derived from birds and plant names like Cinereous, Motmot Blue and Squill Blue. There are over a thousand colour samples, assiduously defined, calculated and named.

Compare and contrast... Pale Purplish Grey or Pale Neutral Grey? Or maybe even Gull Grey?

Colour standards - and our ability to describe and replicate colours - are surprisingly foundational to much of modern life. From the screens we use daily to the clothes we wear. Printing, videography, textile and product manufacturing all rely on precise colour descriptions. We use numbers and letters a lot more these days - unsatisfactory to Ridgway and unmemorable even now.

Why have numbers when you can have ‘Fuscous’, ‘Chessylite Blue’ or ‘Cinerous’?

A squill is a bird. And chessylite is a mineral. In case you're wondering.

You can read the full book online on the website of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives: https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/colorstandardsc00ridg

There are some nice notes on the J. Willard Marriot Library (University of Utah) blog:

https://blog.lib.utah.edu/color-standards-color-nomenclature/